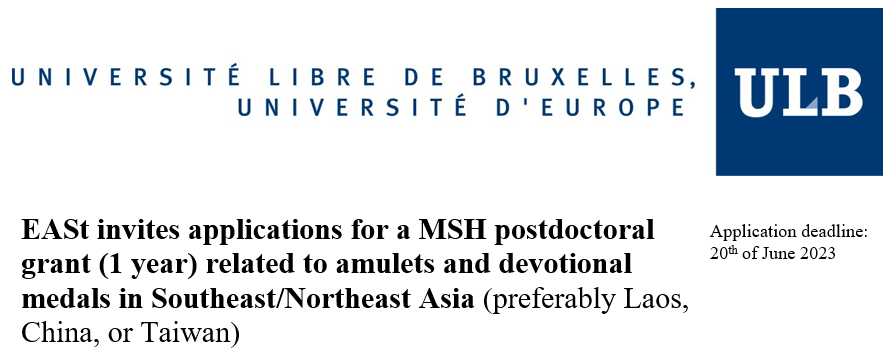

This a rare opportunity to work on amulets and devotional medals of Southwest and Northeast Asia with Pierre Petit at the Université libre de Bruxelles. I’ll copy the announcement in full below. Pierre Petit’s most recent publication, co-authored with Vanessa Frangville, is

Pierre Petit and Vanessa Frangville, Les médailles chrétiennes de dévotion en caractères chinois. Une page d’histoire de la propagande missionnaire française, in Bulletin de la Société française de Numismatique 77/05 (May 2022), pp. 169-176.

Environment

EASt, centre for East Asian Studies (https://msh.ulb.ac.be/en/team/east), is a research unit within the Maison des sciences humaines of the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Belgium. The key role of EASt is to be a central hub of the ULB to foster Asia related activities and research across the university. EASt offers high quality research on current developments in the East Asian region, and established research projects and networks focusing on Asian studies.

The Maison des Sciences Humaines of the Université libre de Bruxelles (MSH-ULB, https://msh.ulb.ac.be/en) is a platform hosting and supporting interdisciplinary research in the Humanities and Social Sciences. It aims to generate new knowledge and research practices by bringing together various disciplines in one place. The MSH-ULB is also an important hub for international exchanges of knowledge. Every year it welcomes several dozen visiting professors and foreign post-doctoral researchers.

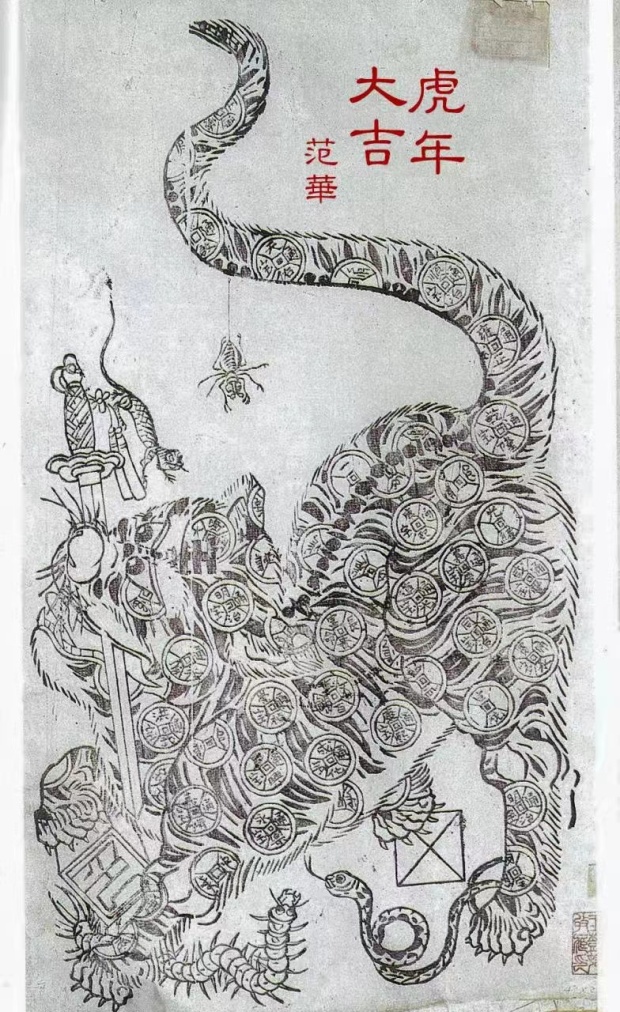

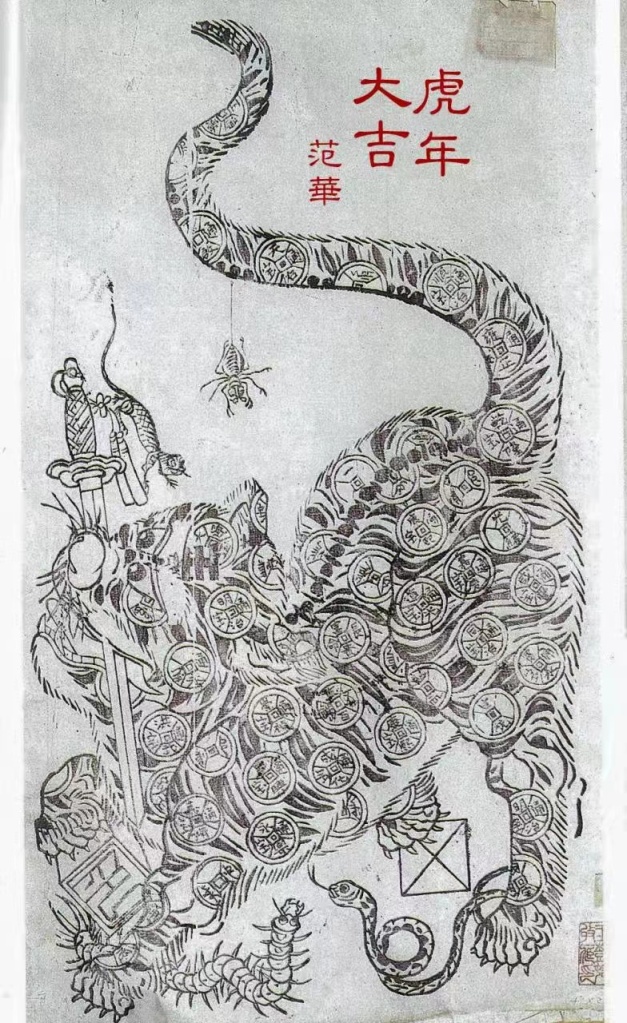

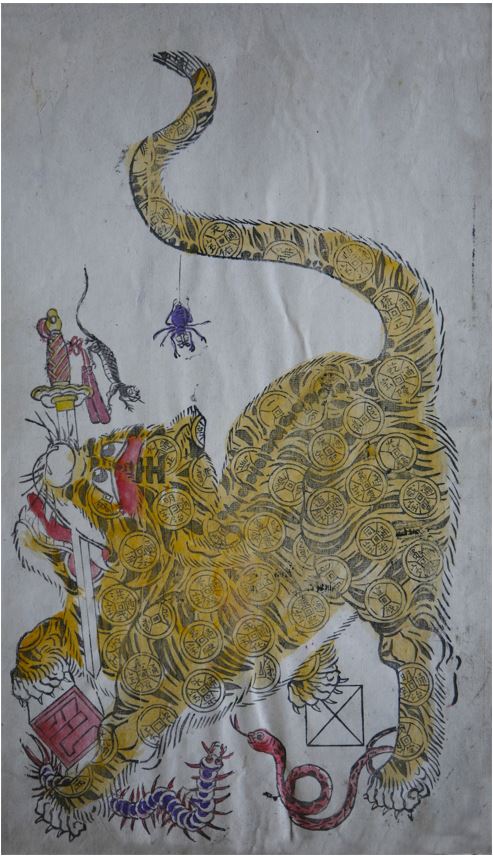

This postdoctoral grant has been designed in synergy with the present research of the promoter, Pierre Petit, who analyses devotional medals through an anthropological and numismatic lens. Christian and Buddhist medals, Taoist (and other) coin-like talismans, and lucky charms are part of everyday life in South-East and North-East Asia. They are used in temples and churches, adorning taxis and private cars, piously conserved in the home, or worn around the neck by the faithful. Often despised as a resurgence of superstition, but nevertheless considered as imbued with some kind of power, they fall beyond the radar of research usually concerned with the more institutional and theological aspects of religion. Taking seriously the challenge of understanding materiality and intimacy in religious practice, the present position will contribute to launching comparative studies on this black spot in the Humanities in the concerned area. Fieldwork research will be conducted in one country – based on the applicant’s competences and preferences – and will be completed, if need be, by historical/numismatic research in the relevant archives and coin cabinets of Europe and Asia.

Objectives

Devotional medals in context

The research will select one specific area/topic – it might be a region, a country, a local devotion or a specific practice – and explore, through ethnographic methods, how amulets or devotional medals are created, circulated, deciphered, blessed, addressed, worn, given sense, provided with a pedigree, empowered with positive achievements, and possibly discarded by those who use them. The applicant will also, in coordination with the promoter, create a corpus of reference of the relevant medals or talismans, which will enhance the research with a historical and numismatic dimension.

The call has been designed for research in Laos, China, or Taiwan, but other proposals related to South-East and North-East Asia will be considered as well. Buddhist medallions in Laos are animated by ceremonies that imbue them with many virtues; their connection with Thai religious figures or religious centres is an interesting issue. Chinese monetary amulets have been collected for a century and a half by Chinese and Western numismatists, but their past and present uses remain largely undocumented. Catholic medals have been distributed by missionaries in China until 1949 and have reappeared since the 1980s, in an often-tense context of relation between the Church and the State – with specific developments taking place in Taiwan.

The applicant is free to elaborate an ethnographic project that fits in with the general topic. The research should ideally lead to the publication of two articles, one related to anthropology and another to material culture or numismatics. Depending on the topic and the area, co-authorship can be considered.

Supervisor: Pierre PETIT, pierre.petit@ulb.be.

Faculty of Philosophy and Social Sciences: https://phisoc.ulb.be/

Laboratoire d’Anthropologie des Mondes Contemporains: https://lamc.centresphisoc.ulb.be/

Any question pertaining to this post and the related application process are to be directed via e-mail to the supervisor.

Post Description

Hiring Institution:

Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Brussels, Belgium

Duration:

12 months (September 2023-September 2024). Besides this internal funding, the research fellow will be invited to apply for a FNRS postdoctoral grant in January 2024, to extend the duration of the research to 48 months. Applying to the FNRS postdoctoral grant is possible only for the candidates who received their PhD after December 2019 (the limit is extended for one additional year per childbirth and/or adoption).

Income:

Approximately 2930€ net per month. Please note that a Fellow’s individual net income after Social Security Contributions can vary in light of their nationality, family status and antecedents.

Requirements

Degree:

PhD in Anthropology, Asian Studies, History, Art History, Numismatics, or any discipline connected to the research proposal.

The PhD must have been awarded after August 2015.

Nationality and residence:

Due to the short length of the contract, non-European applications will be considered in relation to the possibility of getting a work permit in due time (September 2023).

The applicant cannot have been a resident or have exerted his main professional activity in Belgium for 2 years or more during the 3 years preceding the start of the contract (September 2023).

The candidate is expected to settle in Brussels within two months after the beginning of the contract.

Language:

Proficiency in written and spoken English is required.

Knowledge, or willingness to learn French, is a plus.

Speaking/reading any relevant Asian language is a strong point for application.

How to apply

Candidates must send their applications as PDF files to the PhD supervisor’s professional email address (pierre.petit@ulb.be) no later than 20th of June 2023 (17:00 CET).

Applications must include:

- A letter of introduction (statement of motivation and personal interpretation of the research project in max. 3 pages);

- a full academic CV;

- their PhD dissertation and the PhD report.

Key Dates

20th of June 2023: Candidates must send their applications to the relevant supervisor.

23rd of June 2023: Shortlisted candidates will be invited to as Skype interview with their supervisor and the selection committee.

28th of June: Shortlisted candidates will be informed about final decision.

Before 30th of October 2023: Selected candidates to arrive at the Université libre de Bruxelles to start his/her research.